This post is written by Dave Nugent, Cogent Legal’s Senior Producer.

![]() Remember those childhood days of grade school innocence and the excitement generated when it was “Show & Tell” day? Presenters would stand before you, hold something up and then speak to it.

Remember those childhood days of grade school innocence and the excitement generated when it was “Show & Tell” day? Presenters would stand before you, hold something up and then speak to it.

That object was iconic. It immediately conveyed value, meaning and context to the viewer—even evoked emotion—anchoring the speaker’s story to a now-shared understanding between that speaker and his/her audience. A bridge was built. And much of the speaker’s subsequent story would be understood in one or more ways through that shared understanding of the object.

Many trial or ADR PowerPoint presentations could benefit from recapturing the craft of the “Show & Tell.” (In this article, I’m using “PowerPoint” generically to describe any slide-based presentation tool, including Keynote for Mac—our firm’s preferred application—and others that are growing in popularity, such as Google Doc Presentations and SlideRocket.)

Too often, what we should be “telling” we put on the screen. And sometimes, what we should be “showing” we ignore all together in deference to the “telling” in screen text form.

PowerPoint is a VISUAL communication tool. Litigators are among the top in the art in oral presentation, but can benefit from a few “grade school” tips on crafting their supporting visual presentation:

1. Try to walk in the shoes of the audience.

The litigating attorney comes to know every facet of a case in great detail and complexity, and from multiple angles, and unfortunately they sometimes convey that depth of knowledge onto the PowerPoint screen. Think like a juror—what do THEY need to know (and nothing more!)? Craft the presentation according to their needs.

2. Use the “Show & Tell” method to tell the story.

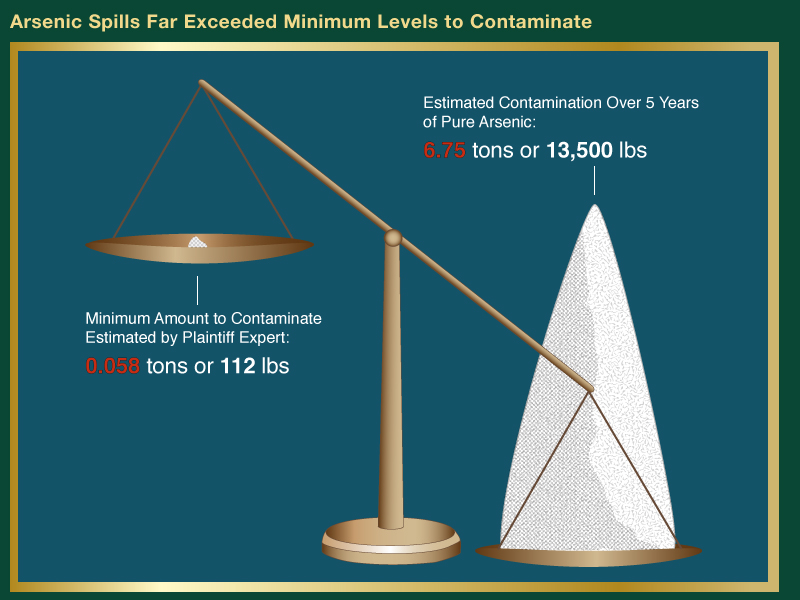

Build oral presentations around slides with simple visual graphics (graphs, flow charts, analogies, illustrative diagrams, etc.) that embellish, evoke context familiar to your juror, simplify the complex, imprint the juror or mediator with the point being made, provide foundation, etc. Leave the words for the speaker, not the slide, to orally convey.

3. One slide, one point.

Don’t compromise the cognitive value of simple legibility by trying to fit multiple argument points onto one slide. Allow the jurors, judge or mediator to focus on the points, one slide at a time. This also gives the argument points longevity. Doing otherwise runs the risk of information overload—a chronic PowerPoint problem that shuts down juror attention and retention.

4. Let the title tell all.

Slide titles need to tell the juror WHY they are looking at each slide. For example, instead of “Employees Moved from Corp. X to Y,” better “Corporate Raiding Also Gleaned Trade Secrets.”

The information design approach discussed above was developed by Professor Michael Alley as the “Assertion-Evidence Structure.” The “assertion” would be in the slide’s title, and the “evidence” would be the visual conveyed below that title, in support of the assertion.

Years ago I was tasked with supporting a litigation team who—worst-case scenario nightmare come to life—handed me roughly 80 to 90 slide outlines … ALL of which were text bullet points. Perhaps not coincidentally, the firm they represented no longer exists.

Cogent Legal was voted "Best Courtroom Presentation Provider" for the second year in a row in The Recorder newspaper's

Cogent Legal was voted "Best Courtroom Presentation Provider" for the second year in a row in The Recorder newspaper's

Since people remember little of what they hear, and the most from what they do, the PowerPoint presentation, although it’s in the middle asa “what you see’ technique, is another effective way to get across to triers of fact what they need tp know, hopefully without ‘boring them to death’.

A brief, to the point, explanation of facts or opinion is always the best presentation method.